Sometimes books make us tilt our heads quizically. Take, for example, our copy of the largest ever letterpress-printed bible (Thos. Macklin, 1800). It was owned, for reasons passing understanding, by a notorious gentleman jockey whose death in New Orleans was chronicled minute-by-minute in the press. As with all incongruities, it leads us to question both halves of the connection, viewing and reviewing to see if we got something wrong.

Enter the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, the former Edward VIII of the United Kingdom and his wife Wallis Simpson.

The future Edward VIII as Prince of Wales with Wallis Simpson, taken by Vincenzo Laviosa, ca. 1934.

After Edward’s abdication in 1936 in order to marry Simpson, a divorcée, the couple moved to a house in the Bois du Boulogne (on the western edge of Paris) that would come to be known as Villa Windsor. There they collected books.

The library at Villa Windsor. Our books would appear to be the leftmost volumes on the top visible right-hand shelf (out of order: Peru, Mexico, Peru, Mexico, Mexico).

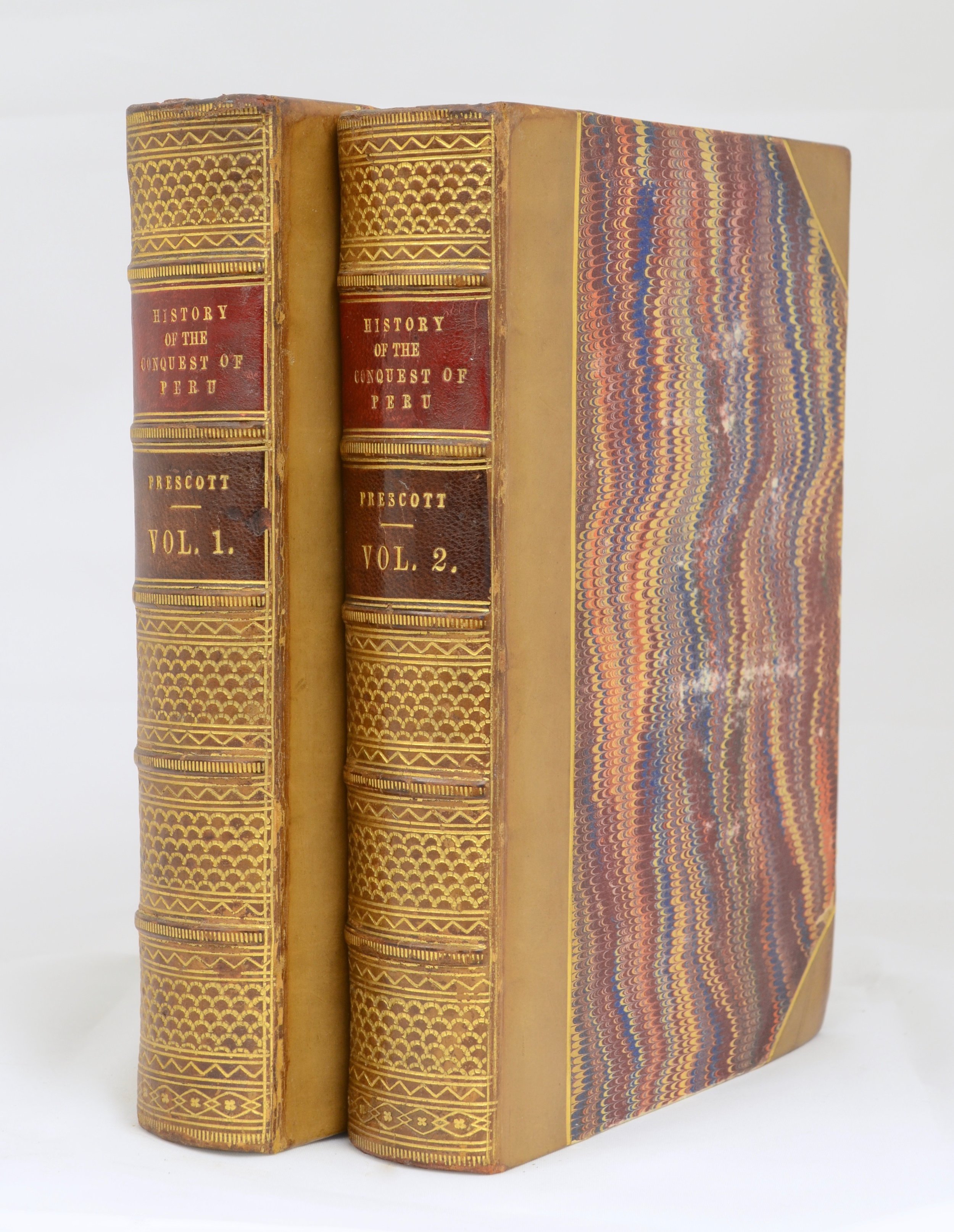

Prescott, William H. History of the Conquest of Peru, with a preliminary view of the civilization of the Incas. Two volumes. London: Richard Bentley, 1847. Second edition.

Prescott, William H. History of the Conquest of Mexico, with a preliminary view of the ancient Mexican civilization, and the life of the conqueror, Hernando Cortés. Three volumes. London: Richard Bentley, 1847. Third edition.

We bought both from the Sotheby’s sale — organized, in fact, by Mohammed al-Fayed and postponed till February 1998 because of the death of his son alongside Diana, Princess of Wales (who together visited the Villa Windsor, as it was known, on the day of their death) — of many of their personal affects, including, famously, the desk at which Edward signed his abdication.

First, the books themselves. William Hickling Prescott belonged to a coterie of New England-born, Harvard-educated men in the early XIXc — including Washington Irving, Thomas Aspinwall (who had his mitts on another of our books) and John Quincy Adams — who traveled extensively and wrote with the full weight of their erudition. Prescott, though, was nearly blind, and did no travel but wrote from his homes in New England — quite the achievement. Prescott established himself immediately upon the initial publication of the Conquest of Mexico (1843) as the absolute Anglophone authority on Latin America, and has remained so right through the XXc and into the present. The book was a wild success and went through two hundred editions in ten languages (Eipper 2000). Fresh from the success of his earlier scientific history, the History of the Conquest of Mexico (first edition 1843), Prescott threw himself into writing a history of Peru, whose kernel was a study of the Inca. After many years of work, punctuated by the loss of his brother and father, Prescott brought Peru to completion in March of 1847; the present item is the second edition of the same year. As with Mexico, Prescott not only consulted primary documents in favor of earlier scholarly accounts, but also included them (untranslated) in an appendix (pp. 435-472).

Both sets are what we might call “handsome” bindings, fitting for the à l’anglaise Villa Windsor. They were owned by the same man, an E. Moore, whose ownership signature is at the upper edge of the title page of each volume.

Perhaps they were bought from him and subsequently bound in the same manner: with marbled boards and matching marbled edges of the text-block.

Yes, the books look as though they should be in the library of a former British monarch living in France — a look to which we might all aspire — but really, how and why did the arrive there? In the first volume of Mexico is a slip from the bookseller G. Martin of the 9ème arrondisement of Paris.

A man of the same name still sells books at that address; an inquiry to him some weeks ago remains unanswered. M. Martin is, at least, the likeliest suspect for the source of the five volumes: the Duke and Duchess (or their agent vel sim.) purchased it there. My guess is that it was in fact the ducal couple, since we have another item of Hispanophone interest purchased at the same sale: a pretty 1923 Don Quixote. The interest was perhaps planted during the time the Duke and Duchess spent in Spain at the outbreak of the Second World War. Perhaps it flourished in the time they spent in the Americas when the Duke was the governor of the Bahamas. Perhaps this is all whimsy, but it does really encourage us to look a bit slower.

Collation:

Peru

Octavo (8 3/16” x 5 1/4”, 207mm x 134mm).

Vol. I: a2(–a1) b-c8 B-HH8, binder’s blank [$2]. 257 leaves, pp. iii-iv v-xxxvi, 1-3 4-480.[=xxxiv, 480] Two engraved plates.

Vol. II: a2(–a1) b8 B-GG8 HH4 II8 KK2(–KK2), binder’s blank [$2]. 254 leaves, pp. iii-iv v-xx, 1-3 4-490.[=xviii, 490] Two engraved plates.

Mexico

Octavo (8 3/8” x 5 3/4”, 209mm x 134mm).

Vol. I: binder’s blank, a8(–a8) b8(–b8) B-2E8 2F4 2G2(–2G2), binder’s blank [$2; –a2]. 235 leaves, pp. iii-v vi-xxx, 1-3 4-442. [=xxviii, 442] With two engraved plates, one folding (a map).

Vol. II: binder’s blank, π8(–π8) B-2E8 2F4, binder’s blank [$2]. 227 leaves, pp. iii-v vi-xvi, 1-3 4-439, blank. [=xiv, 440] With two engraved plates, one folding (a map).

Vol. III: binder’s blank, π8(–π8) B-2A8 2B4 2C-2G8, binder’s blank [$2; –2B2]. 235 leaves, pp. iii-v vi-xvi, 1-3 4-455, blank. [=xiv, 456] With two engraved plates.