[For TMPW, a reluctant converso.]

Those who have visited the shop on Broadway will know that we’re four floors above Rizzoli, one of the loveliest shops in the city. Its roster of events is enviable, and its display is exemplary. It’s easy, frankly, to dismiss the shop as merely decorative; the fiction and cookbooks at the front give way to pendulous and glossy books in slip-cases and shrink-wrap — coffee-table books one might sneer. We true bibliophiles don’t need this rot.

I was one of these people. I scoffed at the illiterati who bought the books and probably never even read them. They placed — not shelved — them opposite expensive scented candles and used them for coasters (USE A COASTER NOT A BOOK).

They weren’t part of the tribe of bibliomanes, or they were at best probationary or junior members.

Reader, here you read my confession of conversion. Yes, I’m writing about very specific books and could keep my nose pointed heavenward, but I offer no conditions or asterisks to my testament: I love large-format photo-books.

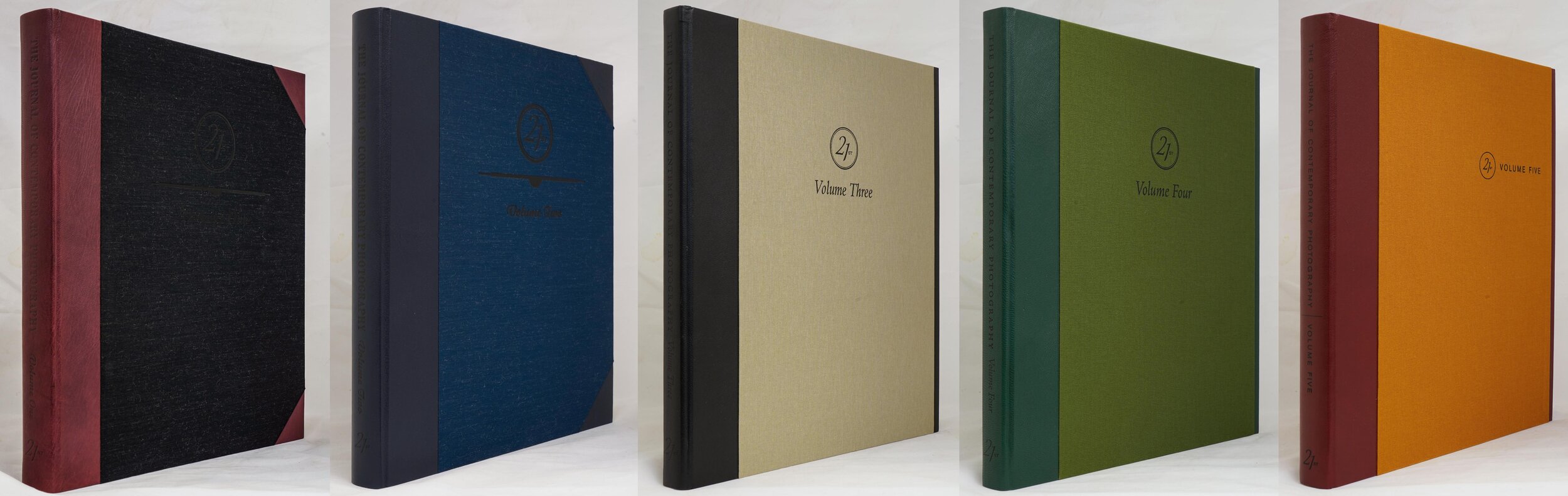

As sometimes, necessity (read: my employer) is the mother of affection. I’d avoided the Journal of Contemporary Photography (JCP) only because there are a lot of them, they’re large and their cardboard boxes are intricate in the unfurling and refurling. The aim of the journal (1998-2003) was, as promulgated by its editor John Wood and its publisher Steven Albahari, “to publish the finest photography being created along with the finest writing about it.” Each was issued at three levels: limited, deluxe and museum. The museum editions come with a suite of loose photogravures, all ready to frame and to hang on one’s wall.

Here’s where I stumbled: surely that was the point of such publications. Surely books are not the ideal way to look at art, or at least not at photography. Yet portability has long been an admired trait of art. Pliny writes of the esteem of pinakes, small panel paintings that were dragged hither and thither and hung on the walls of Philhellene Romans. Icons are somewhat closer to books, sometimes having elaborate concealments, the better for them to be used as devotional tools rather than as adornments. The earliest professional artist named in England is Master Hugo, a manuscript illuminator. Below, a detail of an initial carried out by Hugo from the Bury Bible (1130’s), kindly shown to me by Parker’s Librarian (with my sincerest thanks to Dr. McLaughlin) at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge this summer.

This was, with the perfect vision of retrospection, the beginning of my journey toward the light. Coffee-table books (for want of a less pejorative term) really have their roots in illuminated religious texts; the twin sense that the word of god was precious and that precious images (literally: Hugo demanded the finest pigments for his work — gold at a time when refining was extraordinarily costly, lapis lazuli brought from Afghanistan) were best put in books, protected by pages and bindings and chains and high walls. (One must go to lengths to defend oneself.)

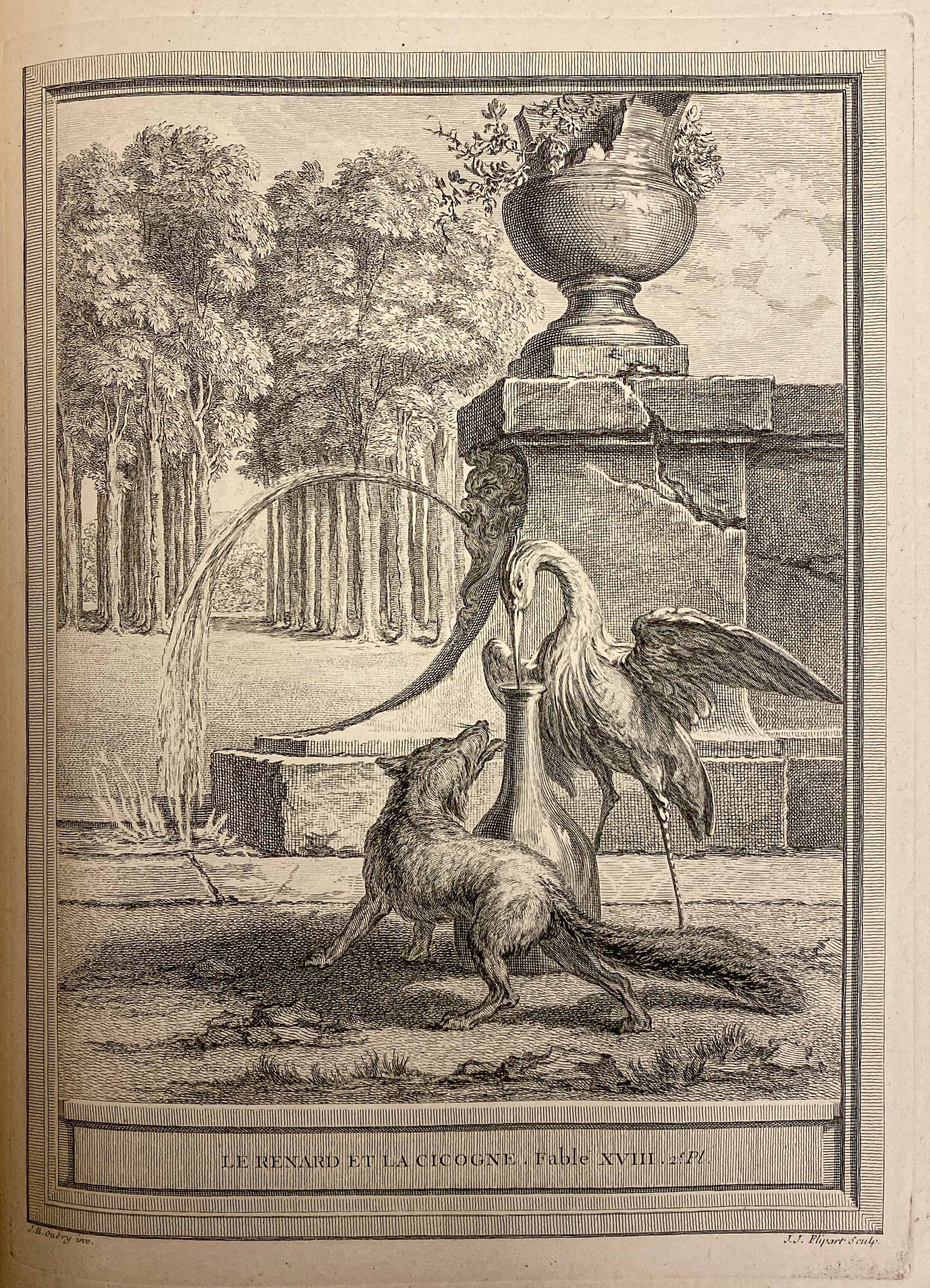

Moving some six centuries later one sees this tradition alive and well in Jean-Baptiste Oudry’s illustrations of Aesop’s fables as translated by Jean de la Fontaine: a four-volume jewel-box of the finest engravings of the era of Louis XV. More profanely, admittedly, than the illuminations of the bible, these illustrations nonetheless gild the wisdom of the ancient sage.

The deluxe edition of the JCP, ensconced as it is within a rich binding inside a clamshell box within a printed carboard case, is a precious thing.

The volume-three striptease: cardboard carton, clam-shell box, book.

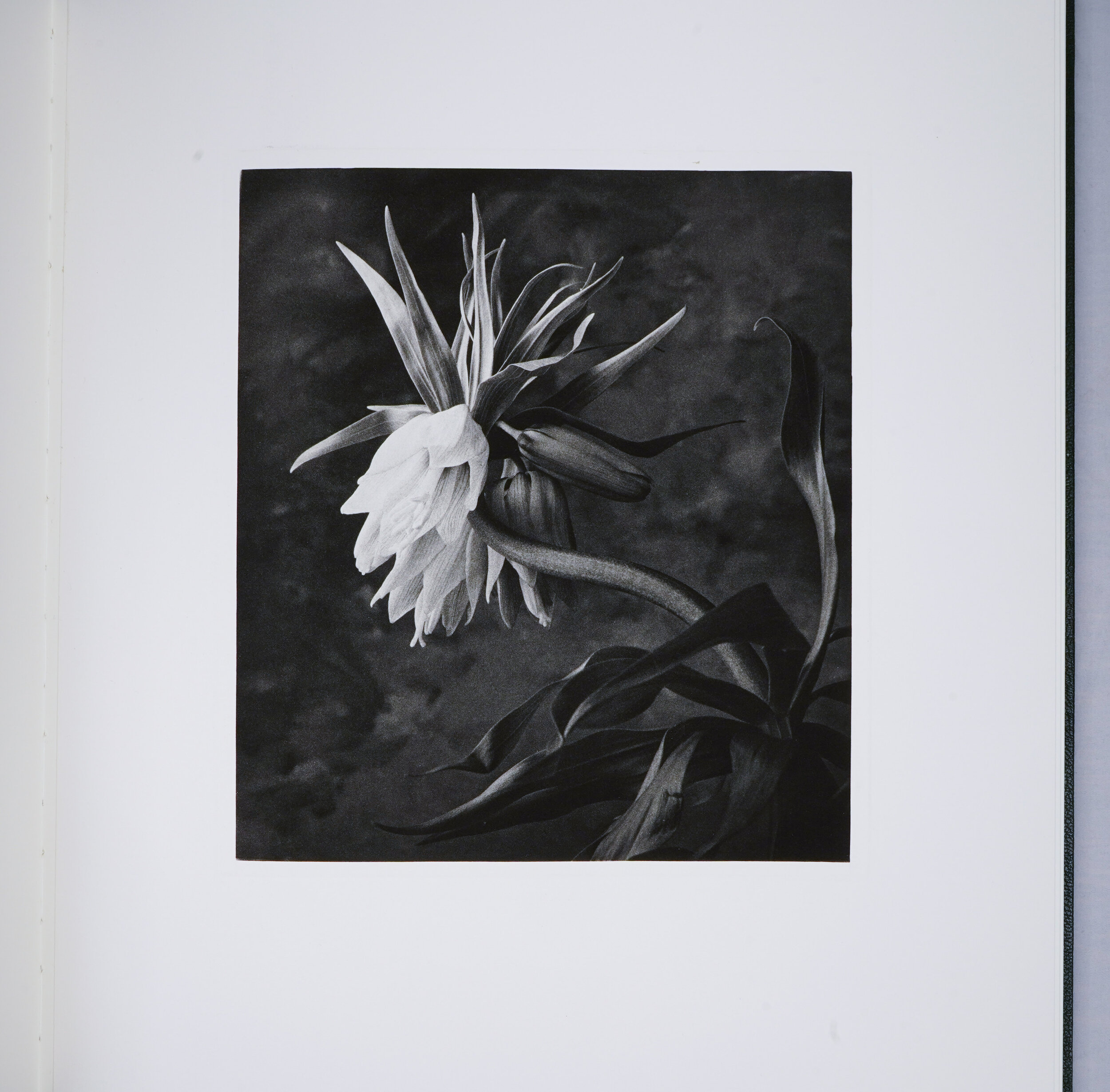

It is letterpress-printed and contains photogravures in addition to ordinary tritone plates. (Photogravure is a process whereby a copper plate is etched according to the exposure of a negative and printed with the resultant differing accumulations of ink in the etched portions.) The quality of photogravures is on par with prints, especially in the hands of its great reviver, Jon Goodman (who carried out all the photogravures in the JCP).

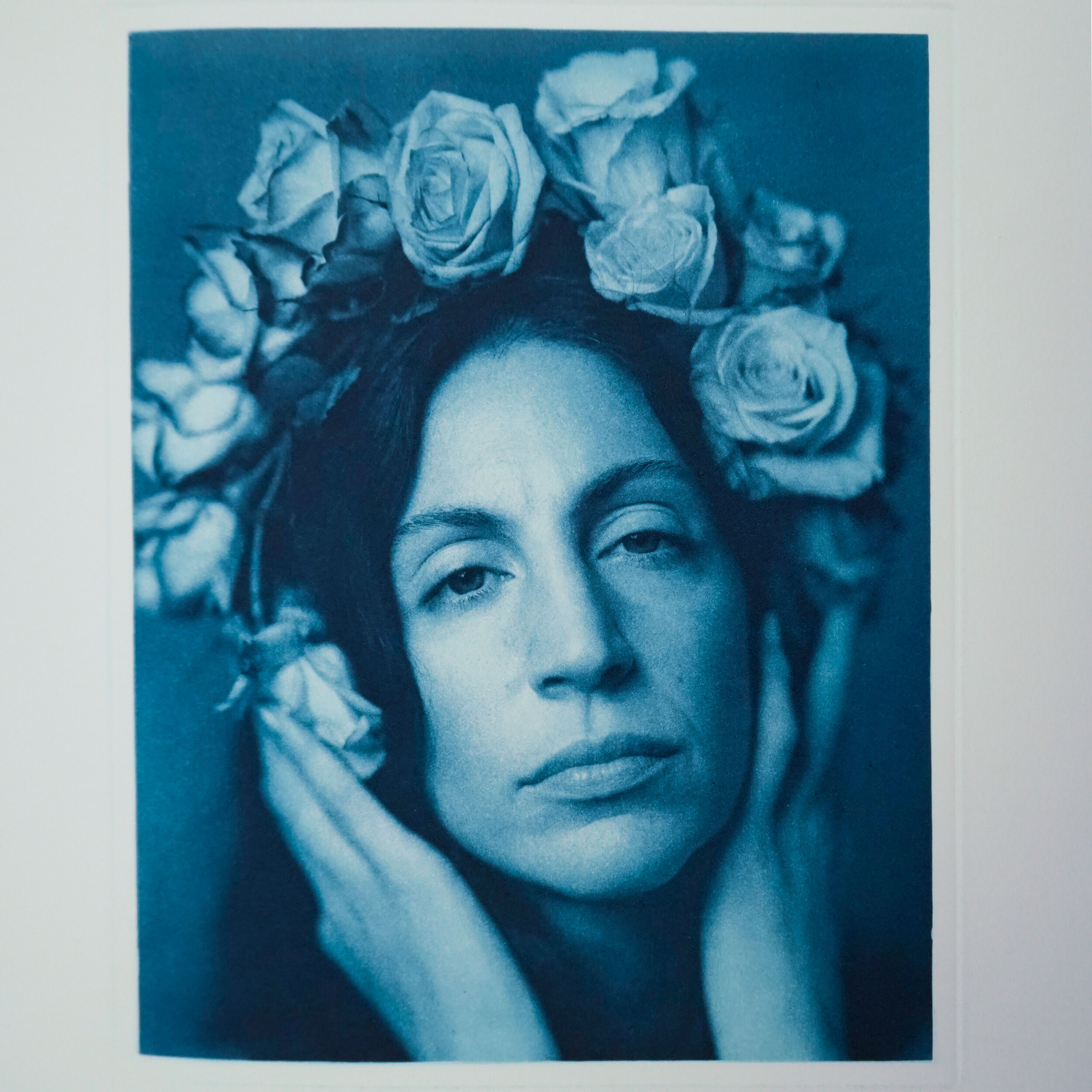

John Dugdale, Longing.

Cy Decosse, Frittillaria.

The very purpose of these books is to convey and to protect these finely printed photographic images, which are susceptible to degradation. Less mechanically, the way in which the reader participates in an image in a book is quite different from the way a viewer participated in an image on a wall. The book invites intimacy and angles, it has no intermediating glass, it can be (gasp) stroked and smelled. It can belong to just one person, it can hide or even disappear. Books — even big ones — are fundamentally related to the hand of the reader — even if the book has to lay on a table to be read.

Photo books — coffee table books — are ultimately private exhibitions. They need to be chosen and to be activated in order to function. My sneer has been inverted, and now I look on the Rizzoli browsers with something like the tittilation of watching men sort through brassières.