It’s pride month in New York, and there is as much to be proud of as there is to mourn. We look to fiction especially for the sensitive treatment of gay sadness; but can we move past Giovanni’s Room and Maurice? Amidst all the lists and listicles of best gay books, I seldom see anything beyond fiction — but there’s more to see. Here, offered with pride, are three queer books.

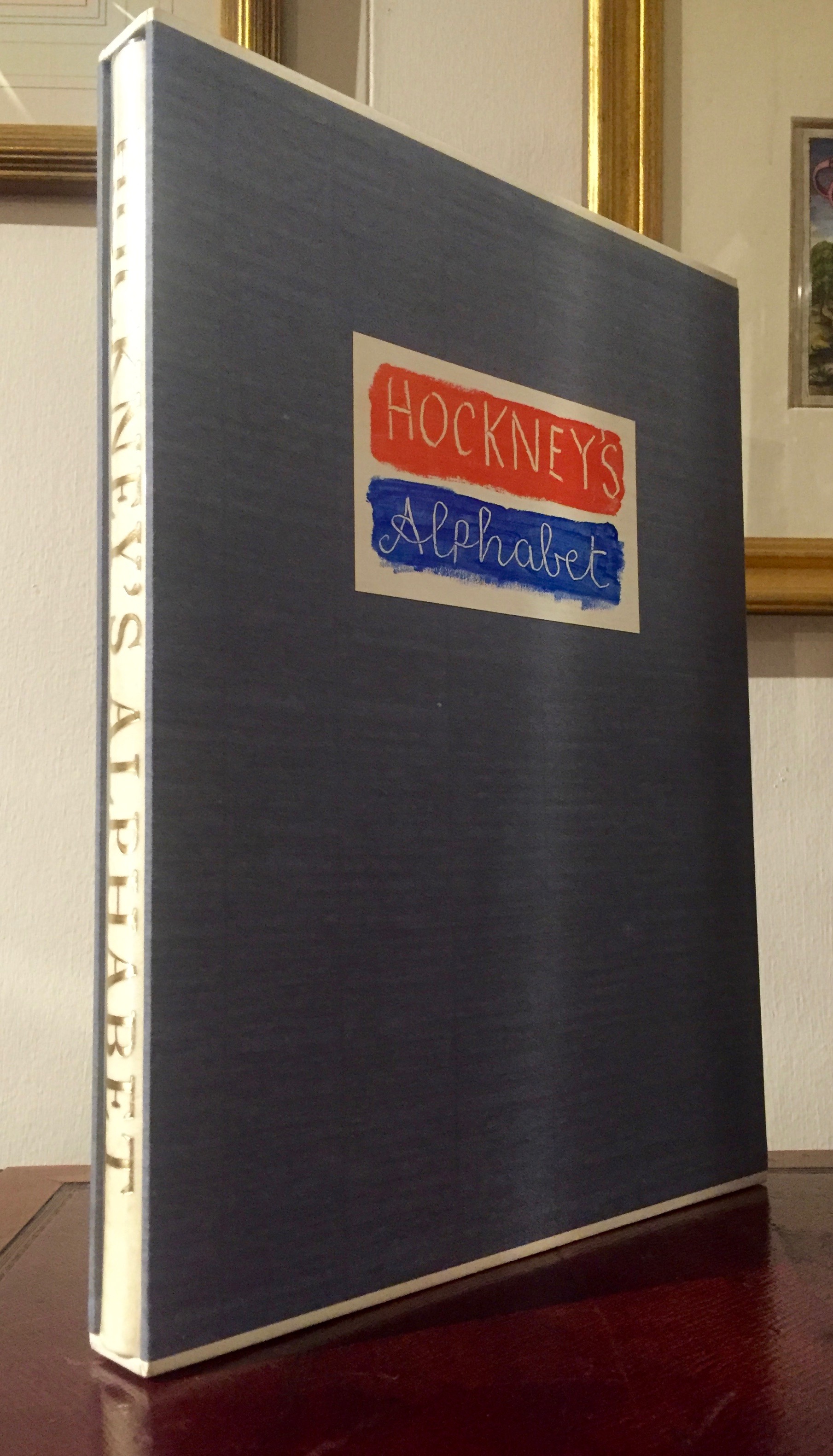

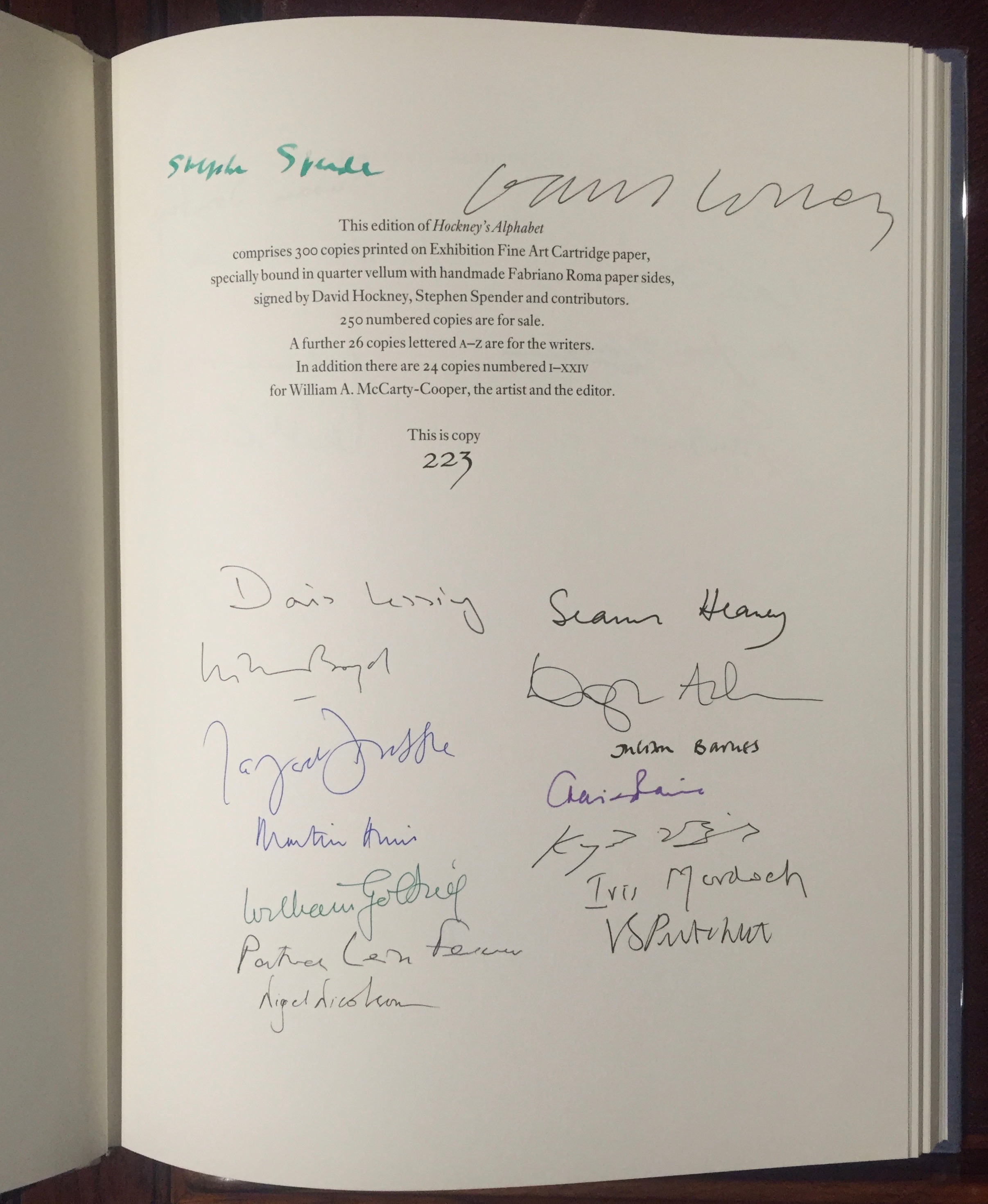

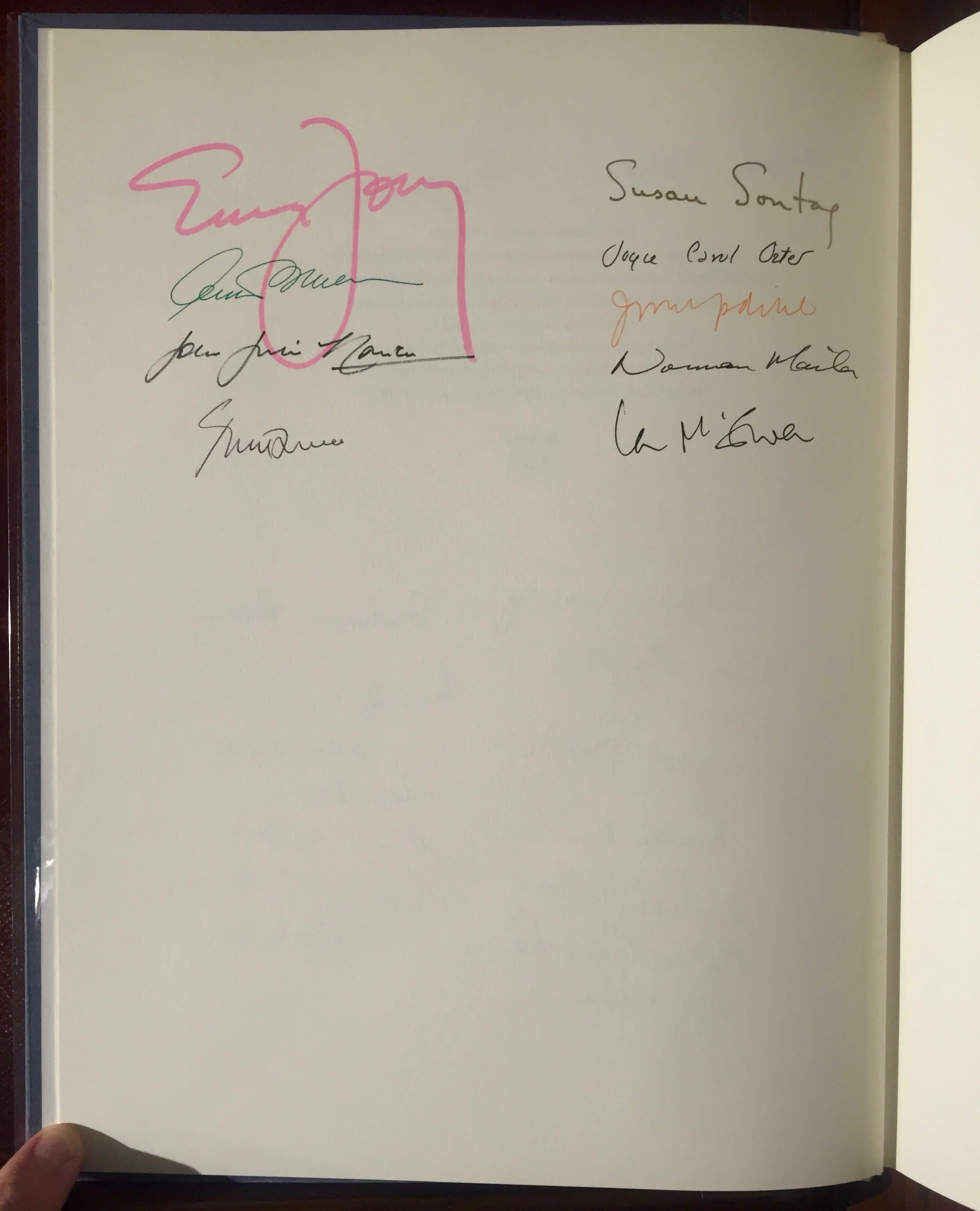

- Hockney, David. Hockney’s Alphabet. Edited by Stephen Spender. London, Faber and Faber for the Aids Crisis Trust, 1991. Numbered 223 of an edition of 250 of a total edition of 300, signed by (most of) the contributors.

Hockney and Spender assigned a letter of the alphabet (plus the ampersand, reserved for T.S. Eliot) to twenty-six notable writers; Spender edited the contributions and Hockney illustrated each letter. The concept is simple but the execution is exceedingly fine. The full list of contributors is stunning (in alphabetical order of subject; those with a † against their names had not signed the book before its issue): Stephen Spender, Joyce Carol Oates, Iris Murdoch, *†Paul Theroux, †Gore Vidal, Norman Mailer, Seamus Heaney, Martin Amis, Erica Jong, Ian McEwan, Nigel Nicolson, Margaret Drabble, Craig Raine, William Boyd, V.S. Pritchett, Doris Lessing, William Golding, Arthur Miller, †Ted Hughes, Kazuo Ishiguro, Julian Barnes, John Updike, Susan Sontag, †Anthony Burgess, Douglas Adams, Patrick Leigh Fermor; additionally: †T.S. Eliot (&), †C.C. Bombaugh (“Alphabetical Alliteration”) and John Julius Norwich (chose Bombaugh’s contribution). *Our copy is additionally signed by Paul Theroux.

Amis contributes a bluntly sensitive essay for “H,” which I reproduce in full:

H is for Homosexual by Martin Amis

When I was nine or ten, my brother and I obliged a slightly older boy – Billy – on a deserted beach in South Wales. It didn’t last very long, and my brother and I took turns, but our wrists ached all day. These few minutes – later totemized by a friend as ‘Martin’s afternoon of shame with Billy Bignall’ – represent my active homosexual career in its entirety. But the memory leads on to another memory: the nausea and despair I experienced when, at the age of thirteen, I saw my Best Friend walking from the games field with his arm over the shoulders of another boy.

I wish I understood homosexuality. I wish I could intuit more about it – the attraction to like, not to other. Is it nature or nurture, a predisposition, or is it written in the DNA? When I think about it in relation to myself, it is not the memory of Billy Bignall that predominates, but the other memory, somehow expanded, so that its isolation and disquiet become something lifelong. In my mind I call homosexuality not a ‘condition’ (and certainly not a ‘preference’). I call it a destiny. Because all I know for certain about homosexuality is that it asks for courage. It demands courage.

The other two are photography books, and need few words.

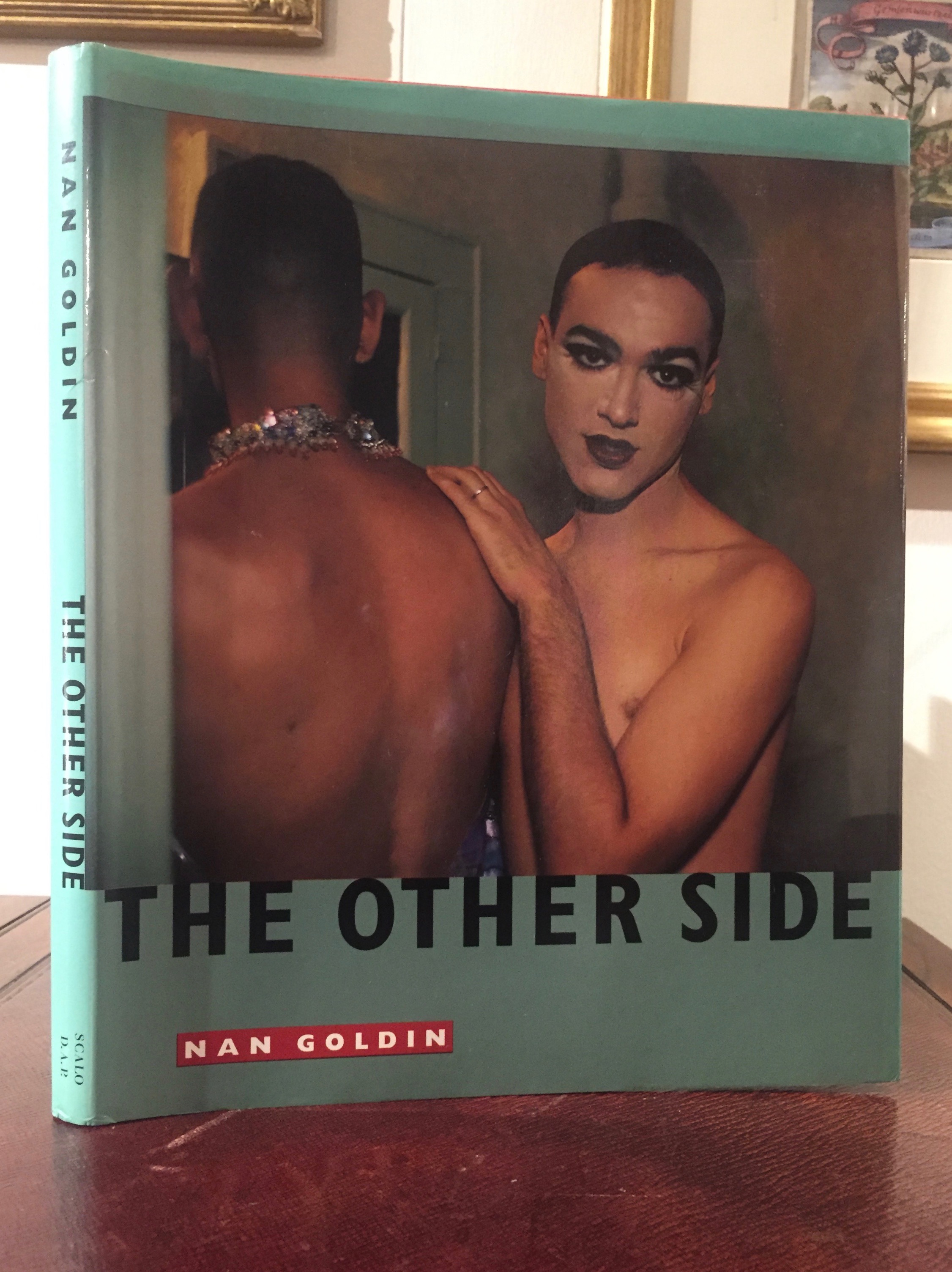

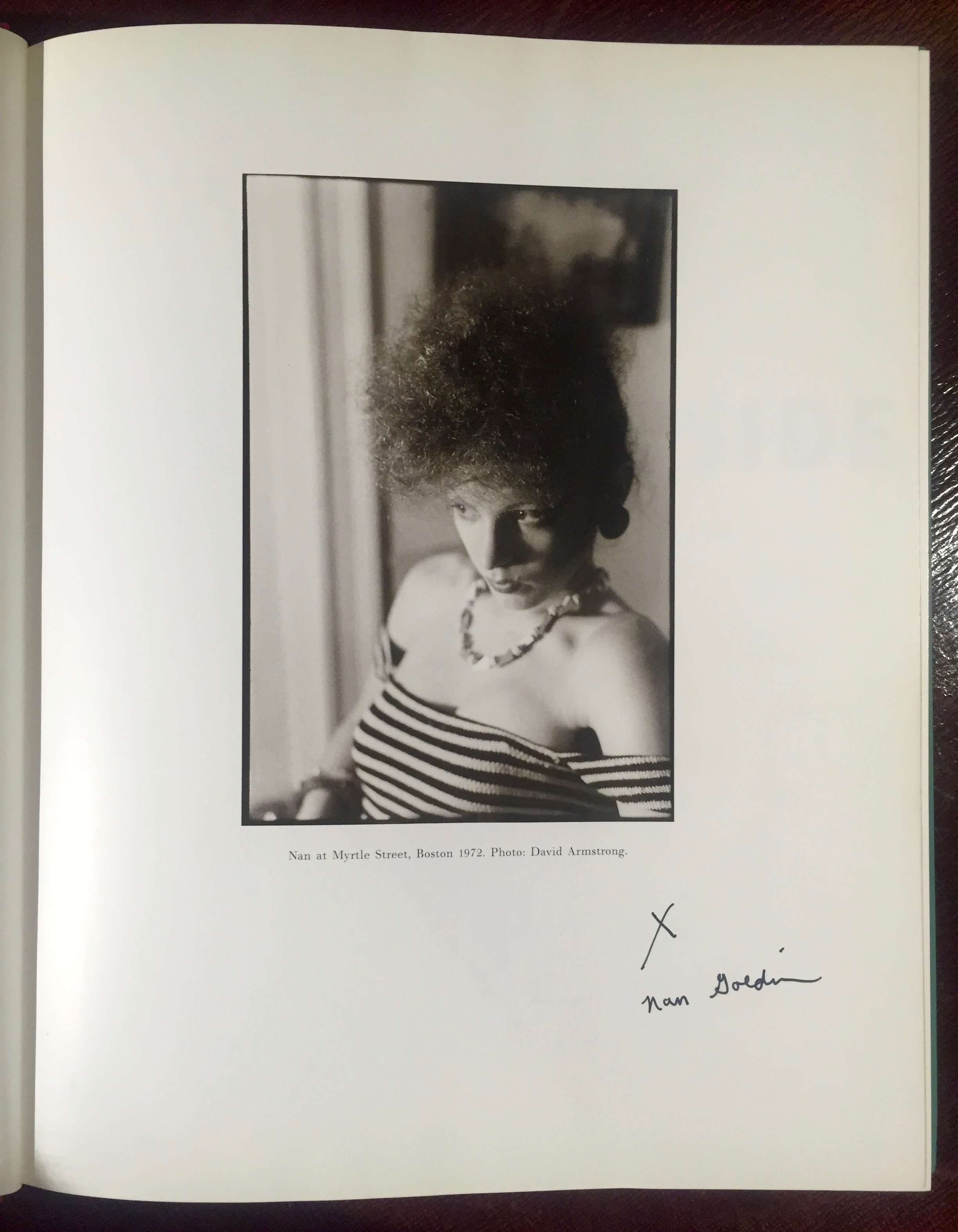

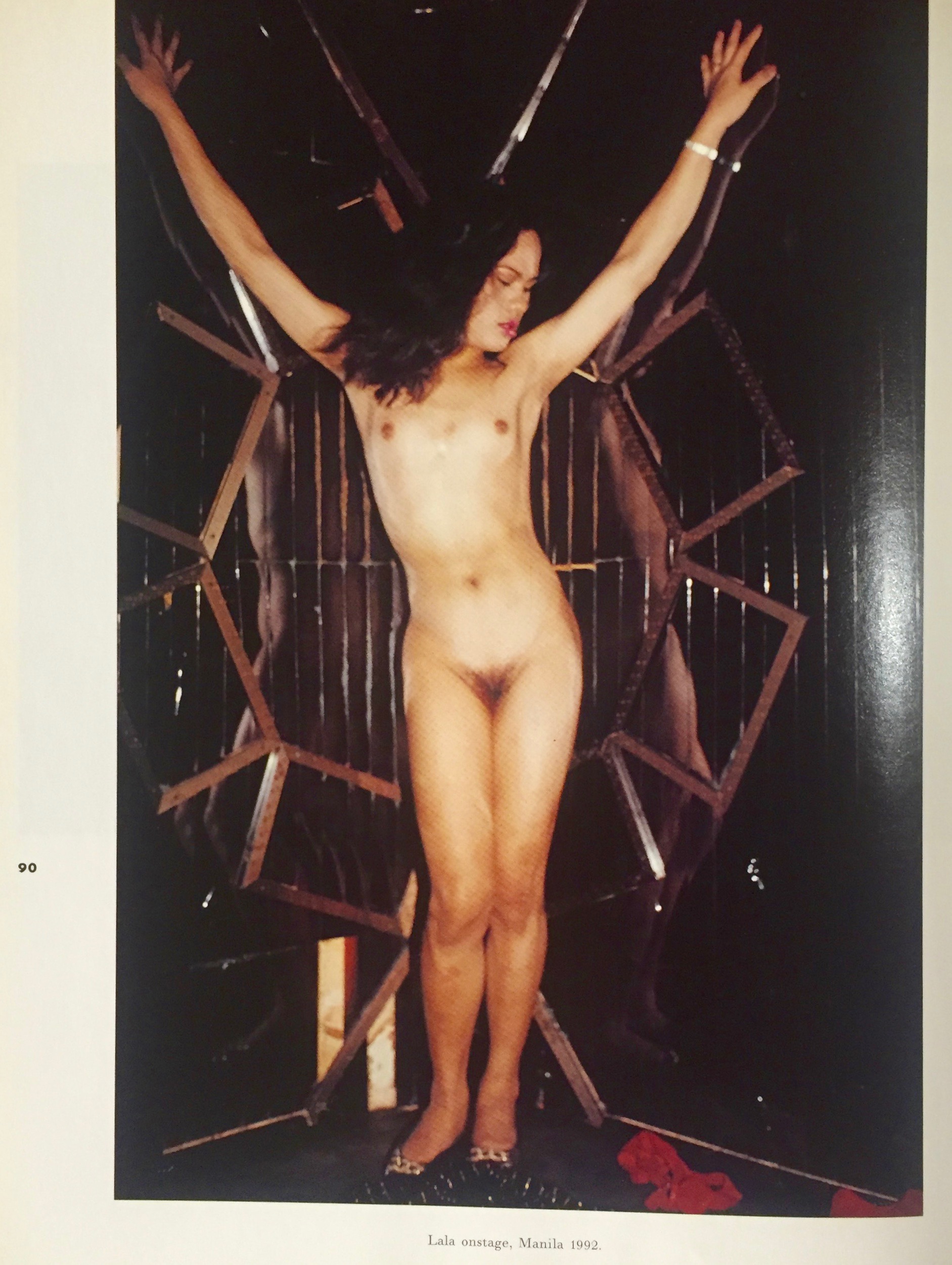

2. Goldin, Nan. The Other Side 1972-1992. NY: Scalo, 1993. First English-language edition.

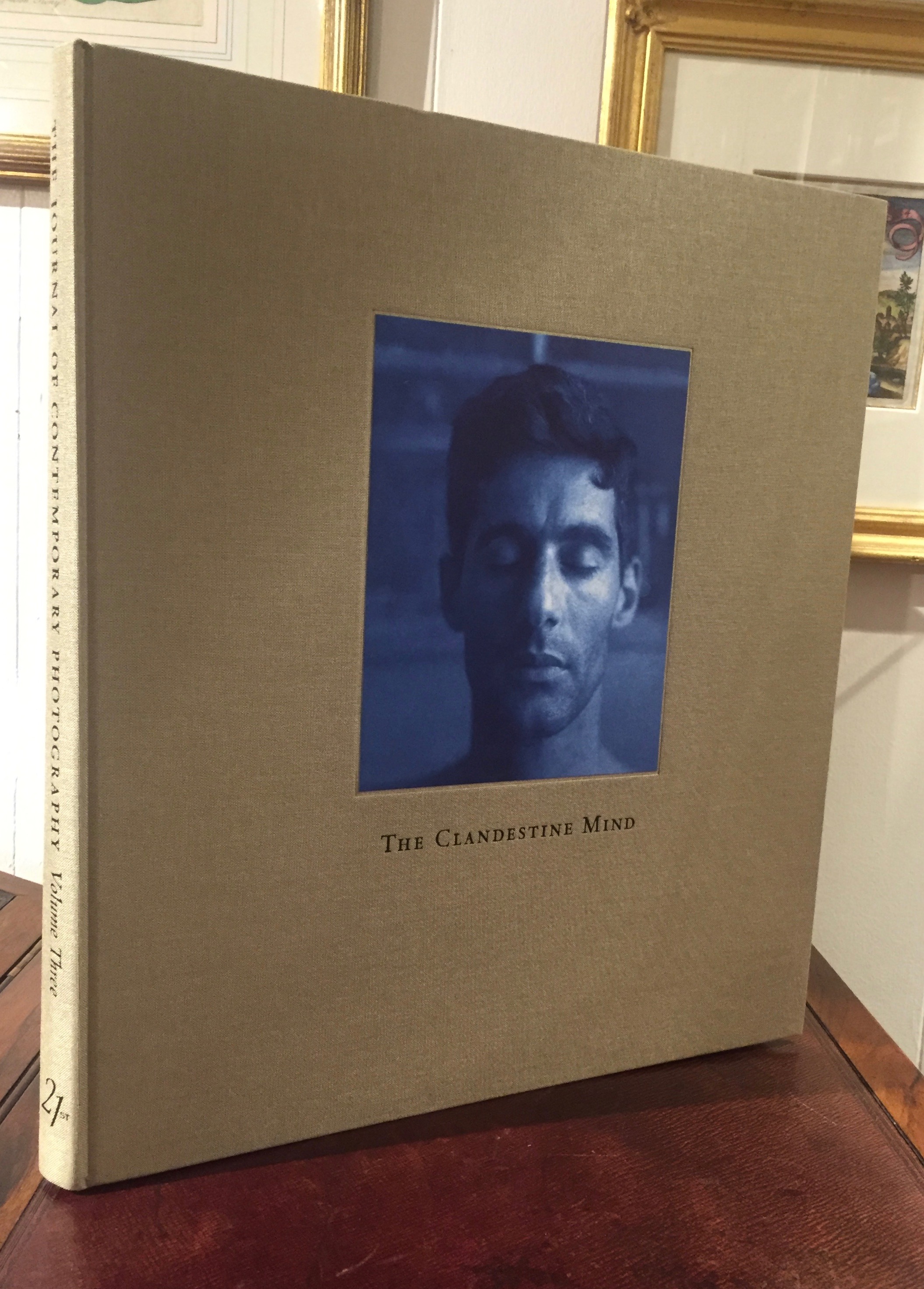

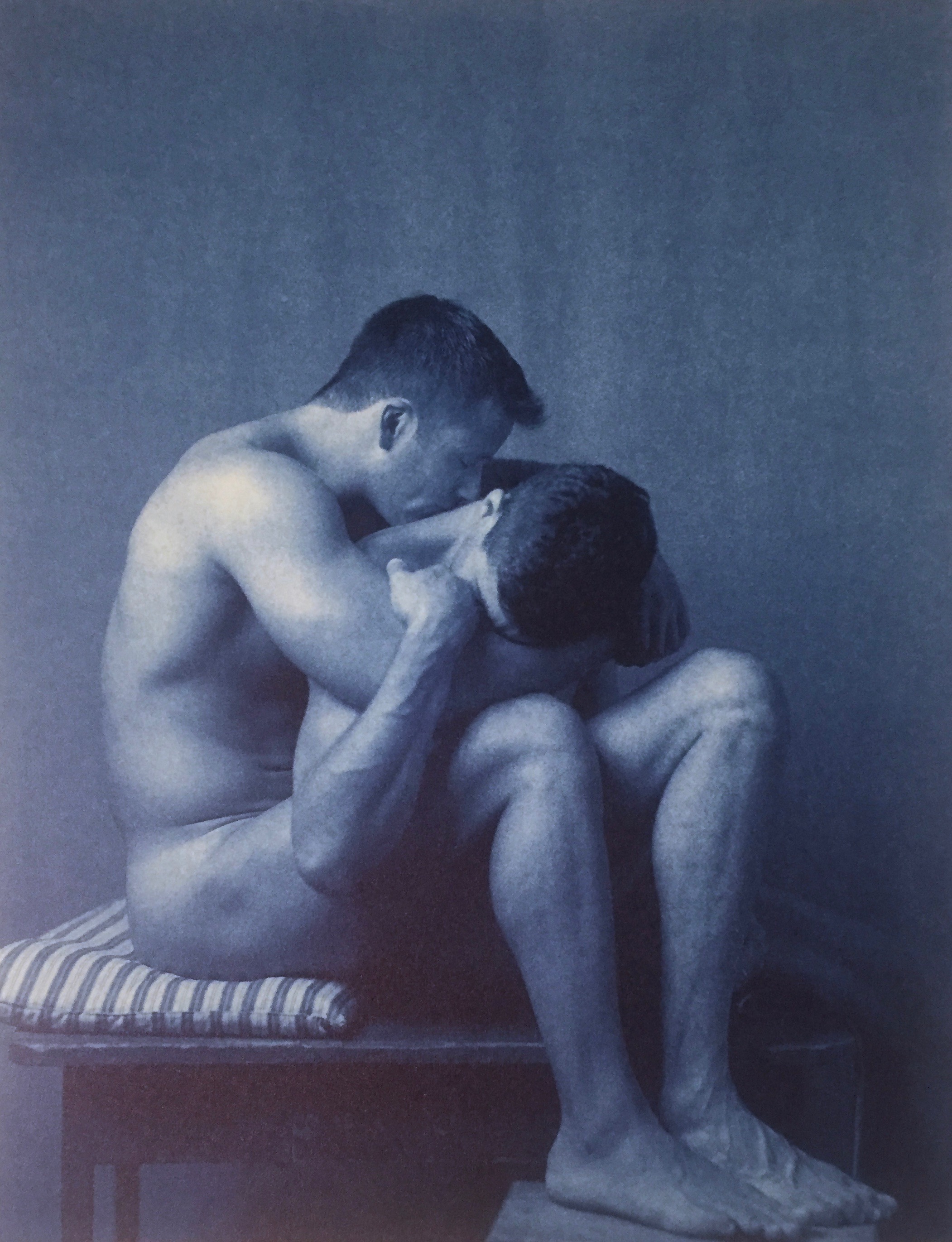

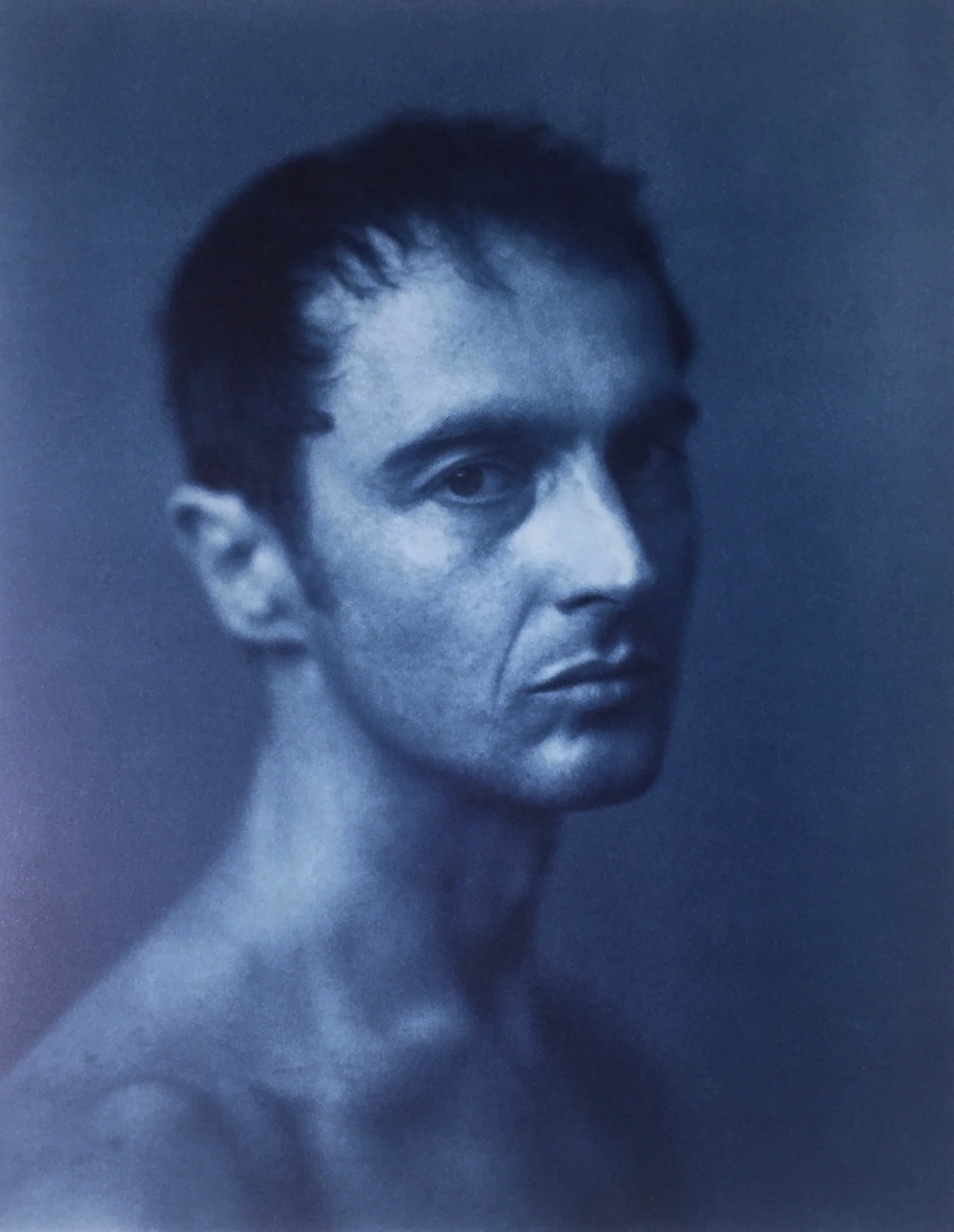

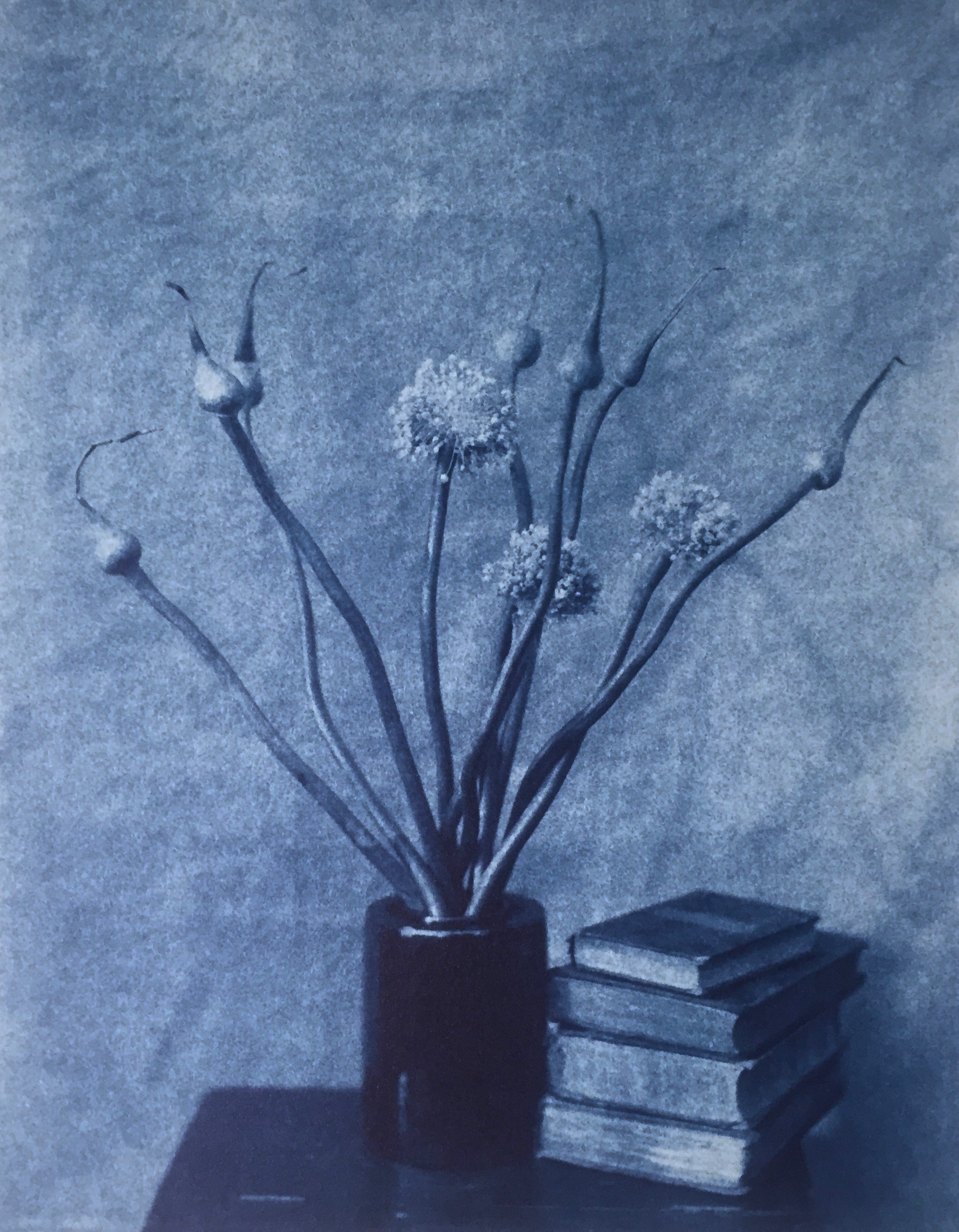

3. 21st Editions. Journal of Contemporary Photography. Volume 3 (The Clandestine Mind). Photographs by John Dugdale. Trade edition. Numbered 76 of an edition of 110, 100 of which are for sale, of a total edition of 165. Signed by Dugdale, Robert Olen Butler (contributing poet), Morri Creech (contributing poet) and John Wood (editor) on limitations page.

Dugdale established the John Dugdale Studio of 19th C Photography and Aesthetics to explore the techniques and ethos of earlier photography. He lost nearly all of his eyesight as a symptom of HIV, and reverted to older methods of picture-making.

As we celebrate queerness this month and every month, let us consider queer aesthetics — what they are, whether they are, and how they came to be. Yes, there is the loud narrative of homoeroticism, to which Dugdale is keenly attuned, but there is more: Hockney’s playfulness, Goldin’s oiliness and her subjects’ various takes on beauty. Altogether these books fragment and refract the monolith of a queer aesthetic, proving that it is not unto itself but entwined with other aesthetics. Queer aesthetics do not fit into a ghetto; Dugdale and Goldin are essentially opposite. Let us take this into account as we celebrate and mourn.