Now that it’s Advent, if you like, or the Christmas season (if you’re in marketing), one’s thoughts turn to family and the giving of tokens of affection. It’s easy to be cynical, as Tom Lehrer was in his Christmas Carol, but I prefer to be solemn and joyous, if I can muster it. If you’re not contemplating the Christ-child, you can at least take the time from work and contemplate, well, something else. It seems to me that, on balance, most old books have been gifts within families; this is quite significant. I have elsewhere outlined my theory of The Book’s Progress:

1. A book is loved and desired and bought.

2. A book is passed down, and loved for being loved by the donor.

3. A book is passed down and number of times, and becomes set-decoration, or, more optimistically, a hollowish token of beauty and erudition.

There are, of course, exceptions. Perverse as it may seem, I spend a little too much time thinking what I would rescue from the shop were there a fire. My answer isn’t our most valuable or the rarest or the most consequential, it is, though, the most constant and potent source of joy to my eye:

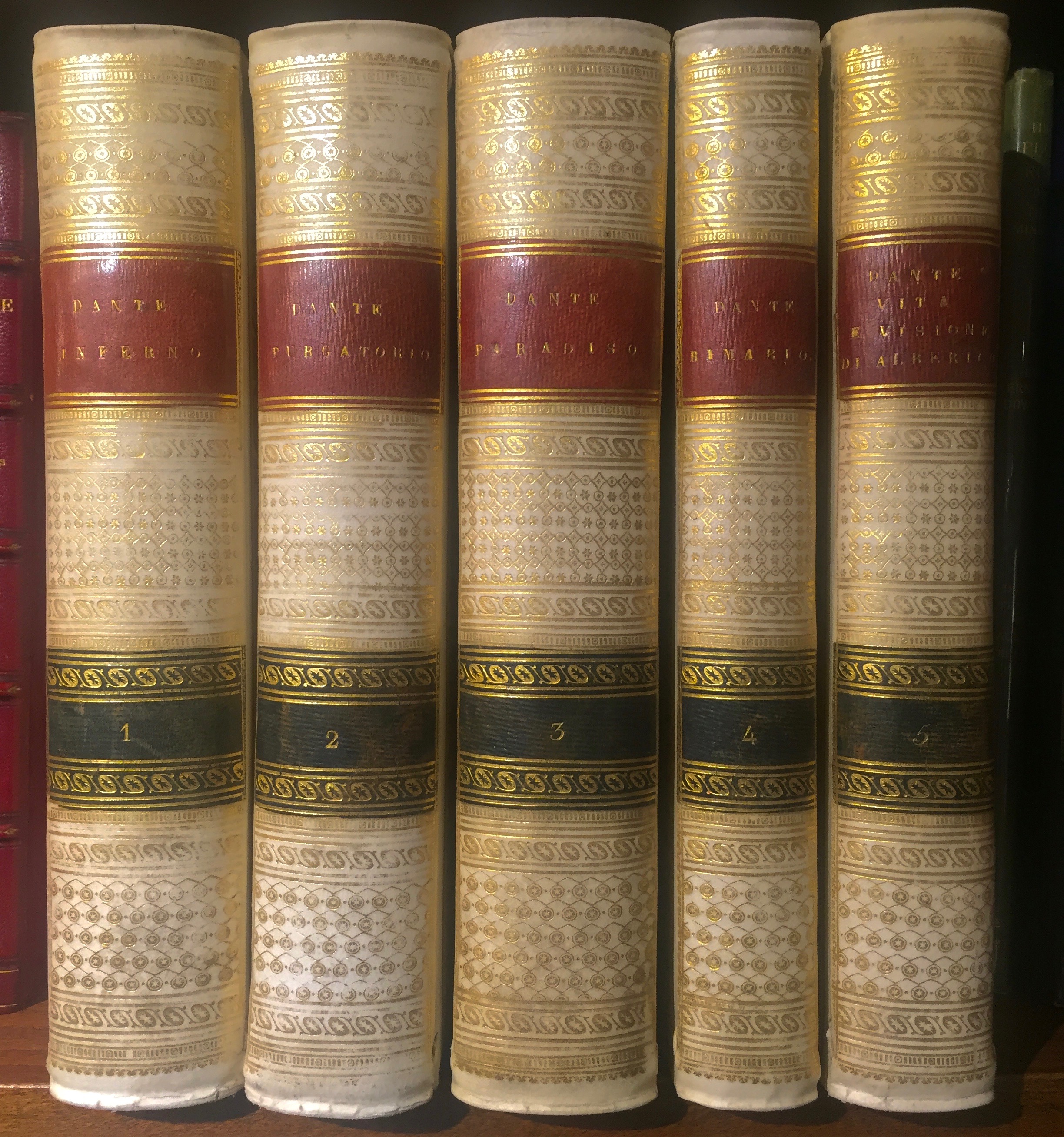

Dante Alighieri, ed. Baldassare Lombardi. La Divina Commedia di Dante Alighieri col comento del P. Baldassare Lombardi M.C. Ora nuovamente arrichito di molte illustrazioni edite ed inedite. Five volumes. Padua: Tipographia della Minerva, 1822.

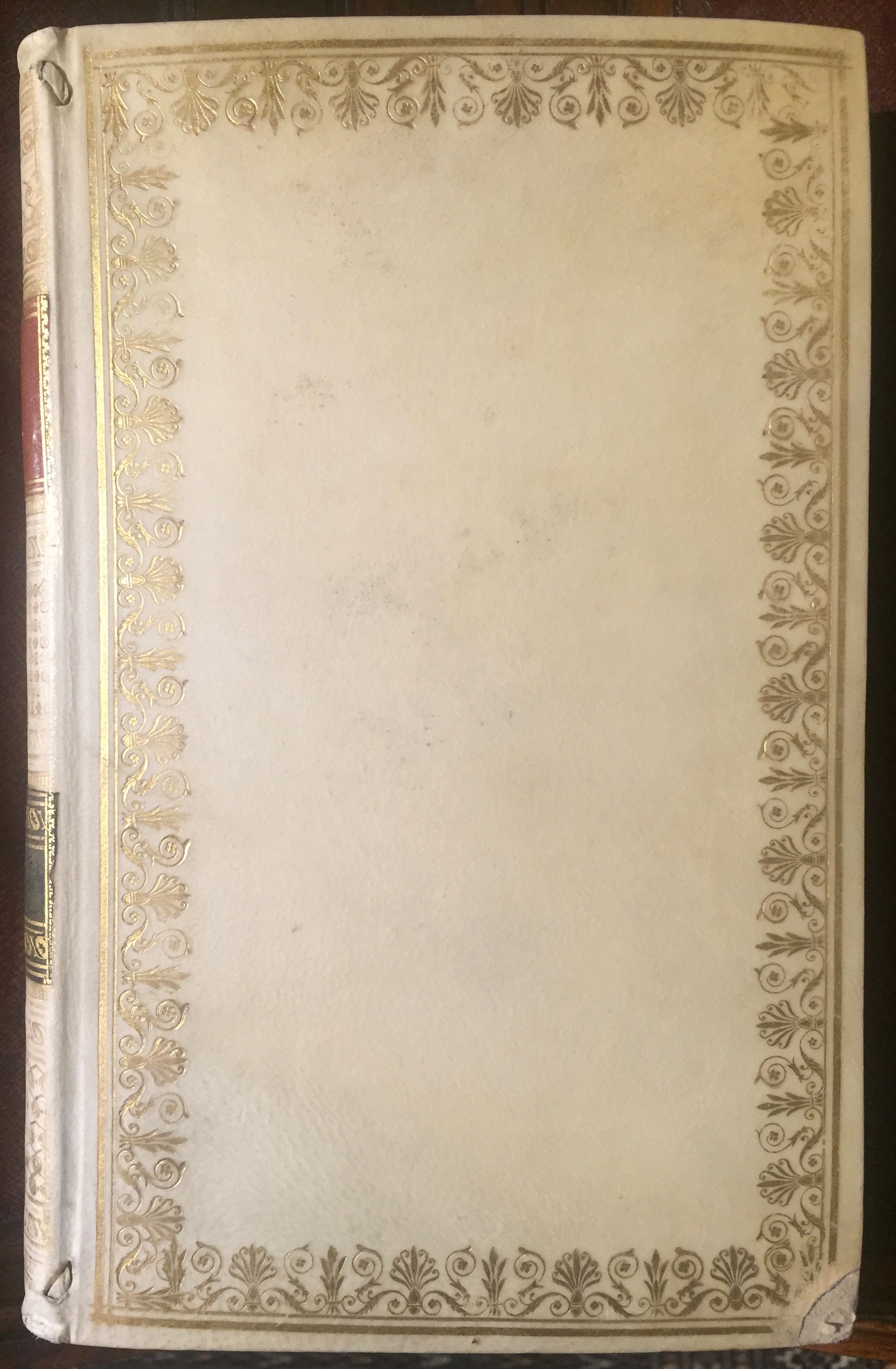

Bound in contemporary vellum, stab-bound, the spines and covers are extra-gilt, with jolly red for title-piece and deep deep blue for number-piece. When we bought it, it was nearly coal-black, but with great timidity — perhaps temerity? — we cleaned it Elgin-marbles-style (i.e., with good sense), and now it truly glows.

Dante is, of course, a natural subject for Christmas (no in-laws–hell-fire jokes, please); so much of the narrative of descent and ascent is likened to birth and redemption. More poetically (than Dante?), I can see these volumes flickering in the light of a fireplace, their bow liquid at their heels.

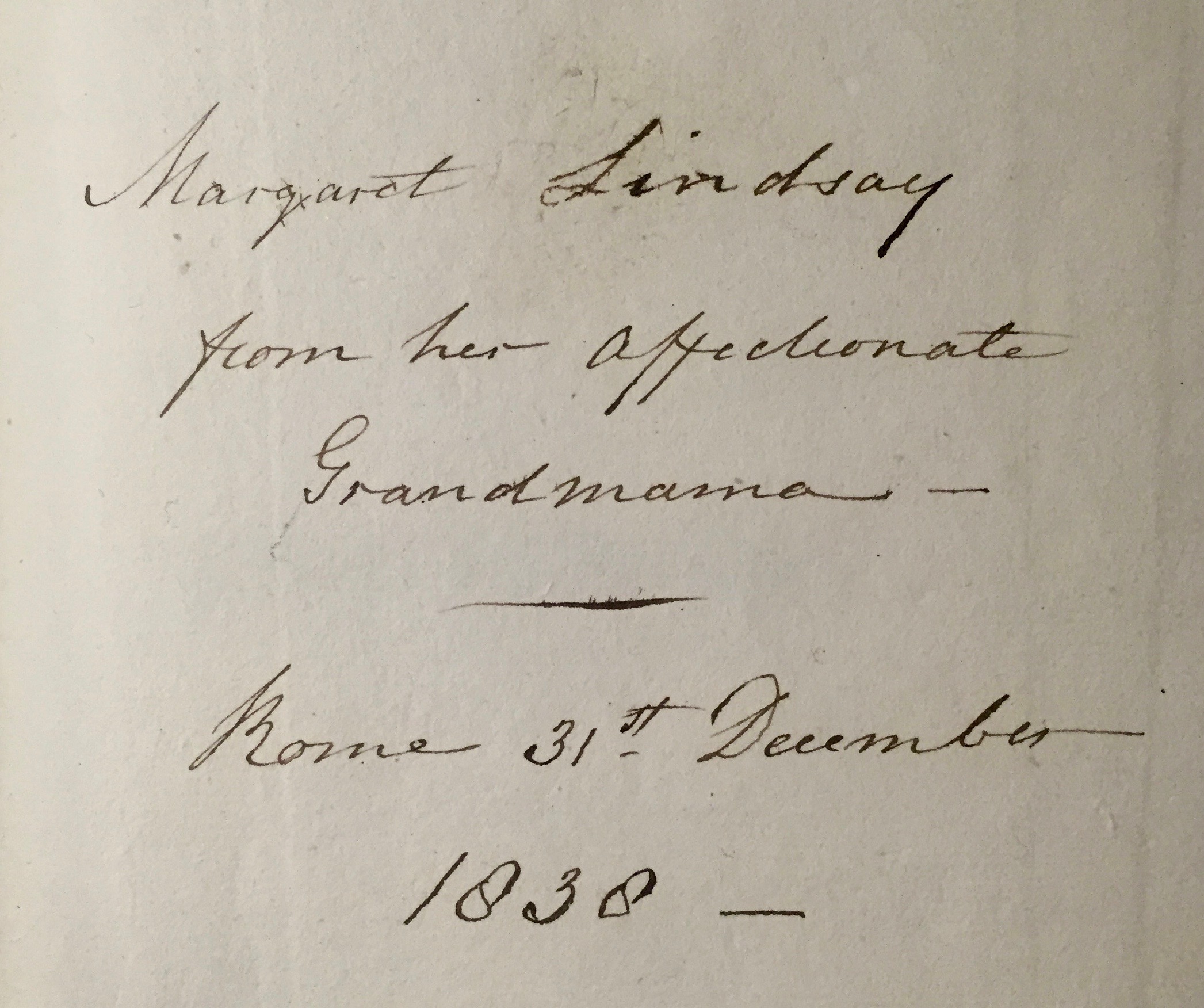

A gift-inscription on the first free end-paper of each volume reads:

Margaret Lindsay

from her Affectionate

Grandmama —

——

Rome 31st December

1838 —

What a delightful gift to have received on one’s Grand Tour. But who was this Margaret Lindsay, and who her Affectionate Grandmama? Margaret Lindsay was born 31 December 1824 (what a fourteenth birthday present!), and received this set from her maternal grandmother, Lady Trotter (Margaret (née Gordon), wife of Sir Coutts Trotter, 1st Bt.); her paternal grandmother (the Hon. Mrs. Robert Lindsay (Elizabeth, née Dick)) had died in 1835. In 1846 Lindsay married her cousin Alexander Lindsay, who would in 1869 become the 25th Earl of Crawford and 8th Earl of Balcarres. The Earldom of Crawford is among the oldest in the United Kingdom. The 25th Earl and his son together built up the Bibliotheca Lindesiana, which at the turn of the twentieth century was one of the foremost private libraries in Europe. The present item does not bear a bookplate of the Lindesiana, perhaps because it remained in the personal collection of the countess. There are pressed flowers in the middle volume.

It is not hard to imagine why the countess held these books close, perhaps passing them to one of her daughters.

In the face of all the Tickle-Me-Elmi and Ex-boxes, let us all hope to receive books of beauty, and to give them to our daughters and granddaughters.