In the year 1800, Thomas Macklin published a huge bible.

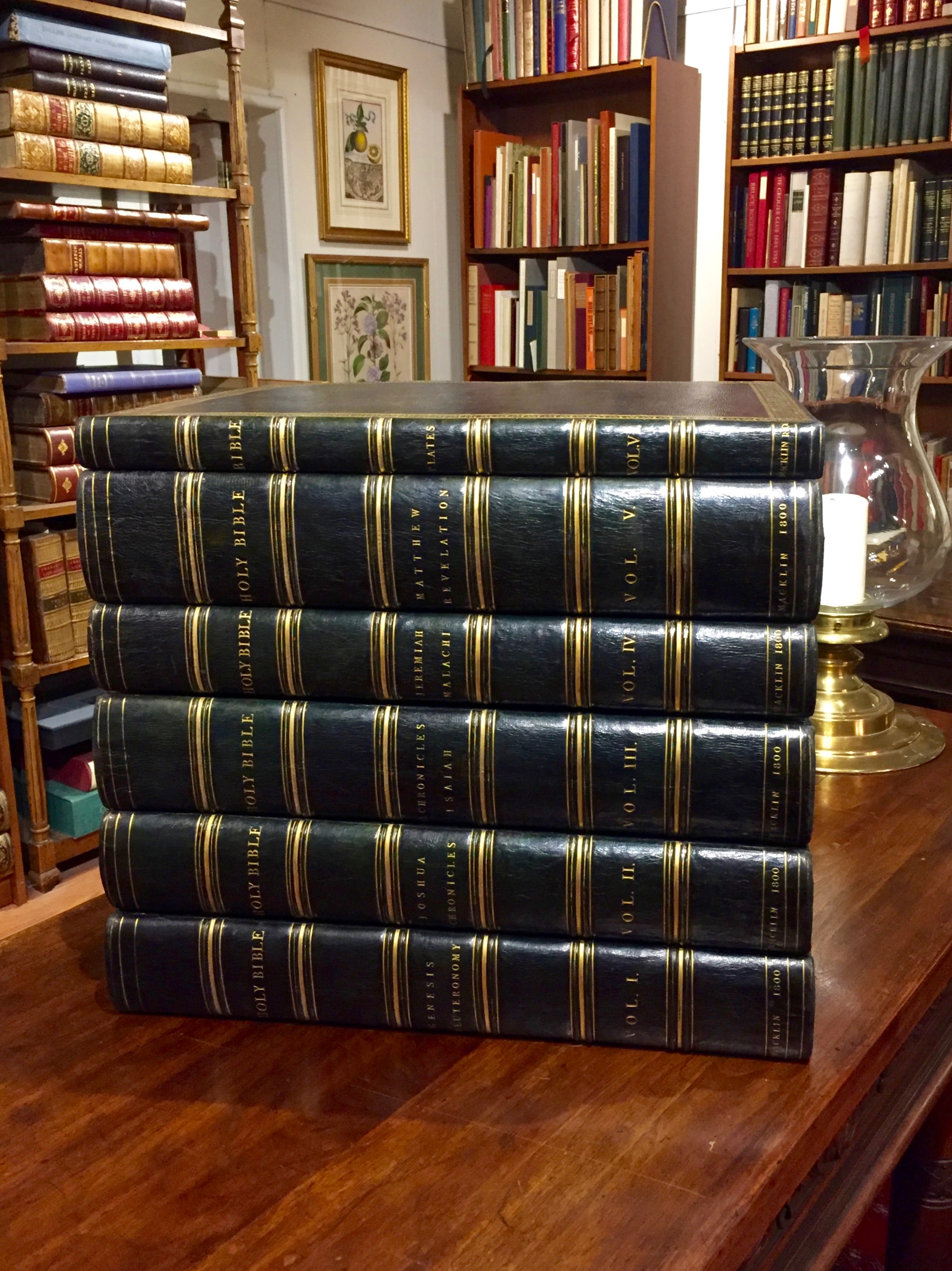

[Bible in English.] The Old [and] The New Testament Embellished With Engravings from Pictures and Designs by the Most Eminent English Artists. Six volumes. London: Printed for Thomas Macklin, by Thomas Bensley, 1800. First edition.

It remains the largest bible ever printed (by letter-press; there’s a Hawaiian bible that’s much larger that was printed via a rather ingenious wheel fitted with rubber stamps). Embellished is an apposite descriptor; in the title it refers to the 70-odd engravings taken from painters such as Joshua Reynolds and Henry Fuseli, but it is a much more sumptuous production than that.

Reynolds's Holy Family. After his painting now at the Tate Gallery.

Thomas Macklin caused a new type-face to be designed and paper to be made expressly for this edition, whose subscribers included most of the Royal Family. The cost to Macklin was reportedly over £30,000 (embellished, indeed). Much of the cost will have been in the production of the plates. At least he didn’t have to pay for a translation (King James took care of that).

Our set was bound by Charles Hering, the London bookbinder who was in several ways the successor of Roger Payne, the greatest English bookbinder of the late eighteenth century. He was patronized especially by Earl Spencer. Lord Byron through rather highly of him. The binding is embellished too, bound in straight-grained deep blue morocco with a dense gilt border, gilt inside dentelles running around all four sides of the paste-downs, and refined gilding to the spine with its six pairs of raised bands.

The present item is in certain ways unusual. First, the list of subscribers follows the text rather than precedes it, as is usual. Second, the text itself occupies five volumes rather than the six called for by the table of contents. Third, the sixth volume contains most of the plates en bloc, instead of having them integrated with the text as is usual. Thus, the set is six volumes in five, plus one. The half-title and title-page of volume six are used at the beginning of volume six (the plates), so nothing is missing. This was doubtless the preference of the original purchaser, who had it so sumptuously bound. A fourth point is the foot-notes, or rather their lack. At the lower edge of several pages foot-notes in a smaller type are to be found, commenting on the text, but nearly are cut off. Oddly, at least one page preserving a deckle edge at the bottom (5Z1 in vol. I) contains a cut-off foot-note, which appears to be unevenly inked. I find it difficult to believe that Hering or his customer would have trimmed the book, whose raison d’être, it might be said, is vastness. Was there an even larger-paper format destined, perhaps, for subscribers? Certainly some copies listed boast slightly larger dimensions than ours, though many cataloguers measure the size of the book rather than of the text-block, which is the dimension of true import. The bibliographies and library catalogues do not mention foot-notes.

Also of interest is the book-plate in all six volumes of George Alexander Baird, of Stichill (1861-1893).

The heir to a great coal and iron fortune built by his grandfather, Baird attended Eton for a year and Magdalene, Cambridge for two, but his great interest was horse-racing. Under the name Mr. Abington (or Squire Abington), Baird was a gentleman jockey, breeder and owner. Baird’s father died in 1870, and the young lad was famously spoiled by his mother. He spent his leisure time in the stables (looking, as a Freudian would doubtless say, for a father-figure) and once he came of age used his inheritance to fund his racing and a gallant lifestyle that drew attention from the British and American press; this only intensified when he took up with actress Lillie Langtry (better known for her affair with Edward VII when he was Prince of Wales). He came to America in 1893 (it is fanciful to hope that he brought this bible with him) and fell ill while prize-fighting in New Orleans, where he died in the St. Charles Hotel. All this was followed with breathless articles in the New York Times, which make for good reading, e.g.:

At first it was believed that he was suffering from a heavy cold, which he contracted when he seconded Jim Hall in his fight with Fitzsimmons. It developed shortly into pneumonia. High fever followed, and his temperature has been as high as 106º. Two female nurses remain constantly by his side, besides his faithful valet, William Monk, and his private secretary, “Ed” Bailey. For two days now he has been delirious, and has taken scarcely any food. Whenever his valet enters the room the Squire in his delirious state jumps up and calls for his clothes, and if it were not for the valet holding him in bed he would injure himself.

March 18, 1893 (the day of his death).

Collation:

Folio (18 1/2” x 14 11/16”, 470mm x 373mm).

Vol. I: π-2π2 A-7E2, binder’s blank [$1; +D2; –2M]. 281 leaves, pp. [viii], [554].

Vol. II: binder’s blank, π2 7F-13I2 [$1]. 240 leaves, pp. [iv], [676].

Vol. III: π2 †A-†8E2 [$1]. 334 leaves, pp. [iv], [664].

Vol. IV: π-2π2 †8F–†13G2 [$1]. 300 leaves, pp. [vi], [594].

Vol. V: binder’s blank, π2 ‡A-‡8S2 ‡8T2(–‡8T2) a-b2, binder’s blank [$1]. 365 leaves, pp. [iv], [718], [8].

Vol. VI: binder’s blank, π2, 67 plates, binder’s blank. 2 leaves, pp. [iv].