Johnson’s Dictionary, sub Aristocracy:

Aristo'cracy. n.s. [ἄριστος, greatest, and κρατέω, to govern.] That form of government which places the supreme power in the nobles, without a king, and exclusively of the people.

Books survive best in environments of benign neglect, which is why so many old books bear aristocratic associations. This is not to cast aspersions on the intellectual attainments of the aristocracy; indeed, it is these very attainments that bring books into aristocratic houses in the first place. Yet such ardor is seldom maintained through the generations, and so the books, much to our gain, become heirlooms and then set-decoration for the good life, the thick couch of dust preserving their gilt edges.

Though American publishers would come to outstrip their English counterparts by the middle of the XIXc, they lagged rather pointedly before. Thus English books were prime desiderata of the American upper classes. And so we come to:

Johnson, Samuel. A Dictionary of the English Language: in which the words are deduced from their originals, and illustrated in their significations by examples from the best writers. To which are prefixed, A History of the Language, and An English Grammar. Four volumes. London: Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, Paternoster-Row; J. Johnson; W.J. and J. Richardson; J. Walker; R. Baldwin; F. and C. Rivington; T. Payne; R. Faulder; W. Lowndes; G. Wilkie and J. Robinson; Scatcherd and Letterman; T. Egerton; P. Wynne; J. Stockdale; Crosby and Co.; J. Asperne; Ogilvy and Son; Cutchell and Martin; Lackington, Allen, and Co.; Vernor and Hood: [sic] J. and A. Arch; Cadell and Davies; S. Bagster; J. Harding; J. Mawman; R.H. Evans; Blacks and Parry; J. Hatchard; J. Booker; W. Stewart; T. Ostell; Payne and Mackinlay; R. Phillips; E. Mathews: and Wilson and Spence, York; 1805. Ninth edition, corrected and revised.

Truthfully, this is not a distinguished edition. It is the first to bear John Aikin’s Life of Dr. Samuel Johnson, but…

1805 is a year of consequence for the Johnsonian, as it is then that the first American edition, printed in Philadelphia, appeared. But by 1819, the London edition of the same year was more desirable to a prominent American abolitionist named Lewis Tappan.

Lewis Tappan.

Tappan (1788-1873) famously represented and secured the freedom of the Africans who were enslaved and transported on La Amistad, whose mutiny in 1839 so advanced the cause of abolition in America. (Tappan was also instrumental in the founding of Oberlin College, the first in America to accept black students.) In 1819, not yet so prominent, he paid the vast sum of $20 (some $350 in current money; the value in sterling, £4.18.9 before duties, is about $900 in current money) to have his brother-in-law, Colonel Thomas Aspinwall, the U.S. Consul in London, purchase and send these four volumes. Tappan very helpfully recorded all this on the second free end-paper of vol. I:

Lewis Tappan,/ April, 1819/ Bought in London by/ Colonel Aspinwall/ Cost £3.13.6 st[erlin]g/ ex[port?] 1. 4. 6/––––/£4.18.0/ or/ $16.33/ Duties 2.69/ ––––/ 19.02/ c. item[?] 98/ [curlicued] ––––/ $20./ 4 vols.

This would soon be small change to Tappan, who in 1841 established the Mercantile Agency. He hired lawyers of repute — including Abraham Lincoln, another prominent abolitionist — to help assess the creditworthiness of those who wanted to borrow money; this would eventually become the great credit firm Dun & Bradstreet.

Susanna Aspinwall Tappan, looking Byronic.

The Aspinwall-Tappans (Lewis Tappan married Susanna Aspinwall) were also a literary family — leaving aside their relation to Benjamin Franklin. Lewis Tappan’s son, William Aspinwall Tappan, was a friend of Ralph Waldo Emerson (who solicited a poem for the Dial) and used to take long walks with Thoreau. Tappan’s daughter, Mary Aspinwall Tappan, lived on an estate in the Berkshires, and on this estate was a cottage in which Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote Tanglewood Tales for Boys and Girls. The estate was named Tanglewood after the book. Miss Tappan donated it in 1937 to the Boston Symphony Orchestra for its summer festival of the same name.

Our Dictionary sits prettily at the nexus of this mid-XIXc artistic community, but its history continues, thanks to a laid-in letter from a later owner, Edward Augustus Bowen. Dated July 14, 1924, Bowen (Tappan’s grandson through his daughter Lucy Maria Tappan) writes to his nephew, Henry Chandler Holt, giving the volumes to Holt’s newborn daughter, Susanna Aspinwall (†2002). There is a rough draft on the of the letter on the back of an invitation card to the high-society wedding of Sarah Tod Bulkley (to Francis F. Randolph) on 3 November (1923); there does not seem to be a connection to the Bulkleys (other than that Bowen was invited to their wedding) — it was perhaps merely a scrap of paper to hand.

The Bowens of Woodstock, Connecticut are an old American family of English and Welsh descent, established in Connecticut already in the early XVIIc. Their “Cottage” — Bowen’s letter notes that it was once called Roseland Cottage, but was called Roseland after the arrival of Ellen Holt in the 1860’s — in Woodstock, CT was a center of upper-class New England summer life, hosting vast Fourth-of-July celebrations and at least four presidents, as well as Henry Ward Beecher and Oliver Wendell Holmes among others.

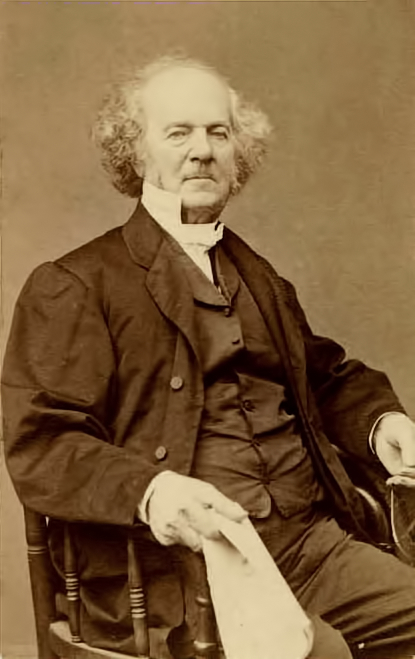

Henry Chandler Bowen, father of Edward Augustus Bowen.

The Holts, too were prominent; George Chandler Holt, Bowen’s brother-in-law (Henry Chandler Holt’s father), was a federal judge for the Southern District of New York, appointed by Theodore Roosevelt.

One ought really to be fined for dropping so many prominent names; sua culpa, sua culpa, sua maxima culpa. Still, the present item is the product of the network of these prominent families, a palimpsest of the reception of the most English of texts into American high society.

Collation:

Octavo (9 1/8” x 5 1/2”, 231mm x 141mm).

Vol. I: binder’s blank, π2(–π1) a8 2a4 b-k4 l4(–l4) B4 C-3G8 3H6, binder’s blank [$2; quarto quires $1]. 470 leaves, pp. [2], 1 2-15, [1], i ii-lxxxvi, [848]. Two engraved plates: a frontispiece and a plate to face the Life.

Vol. II: A2(–A1, ±A2) B-3L8 3M2 [$2]. 451 leaves, pp. [1], blank, [899], [1].

Vol. III: A2(–A1) B-3L8 3M4 [$2]. 453 leaves, pp. [1], blank, [904].

Vol. IV: A2(–A1, ±A2) B-3A8 3B8 (–3B8) 3C-3M8 [$2]. 456 leaves, pp. [1], blank, [910].